Column: First is the worst — why we should delay reopening

March 3, 2021

Imagine this scenario: After almost a year of staying essentially quarantined, you come back to school in-person, meeting other students and teachers for the first time in months. At school, you are expected to trust that other students and teachers likewise have practiced safe social distancing, and expect them to continue minimizing their exposure to the virus. An unhealthy percentage of them do not, and a week later, you feel a boiling anger as you realize that you tested positive for COVID-19 and that you may have infected your family.

Such is the scenario faced by many Palo Alto Unified School District staff and students with the newest reopening plan. Teachers are required to return Thursday, whereas students have a choice, beginning Monday.

The decision to reopen now — the result of a deal agreed to last fall — is too rushed, and ill-advised.

“PAUSD was the first district in our county to return to in-person instruction in October, but even that came after targeted groups had already returned including post-secondary futures [students] at Cubberley,” Superintendent Don Austin boasted to community members at the Feb. 9 board meeting.

But there’s no need to be first. This is not a race.

A risky plan

Beginning next week, up to 50% of students each day will be allowed to return and work from Zoom, in-person. In-person students will be masked, with desks six feet apart and other precautions taken. Those who opt for distance-learning will be tuning in from home on Zoom.

According to Austin, for an average class size of 26 students, that would mean a maximum of 13 students in-person. It includes splitting students up into two groups by alphabet while also not changing schedules, allowing students to stay home if needed.

Hypothetically, a student who is asymptomatic but continues to be contagious could go to school. Due to the lack of a cohort system in the plan, this student would meet many other people throughout the day, and may unknowingly infect the school.

Additionally, teachers may prioritize students who are in-person, introducing a new source to the already growing issue of educational inequality. Students with family who may be at risk may feel like they are at a educational disadvantage if they choose not to opt to return.

Parents’ goals to increase social interaction for their students cannot even be achieved with this plan, as students have to social distance in the classroom, where learning is on Zoom anyway. It is a bad idea to risk having an outbreak in order to have very limited social activity — that’s inherently a bad tradeoff.

Aspirations for vaccinations

A key issue that the current plan fails to address is vaccinating teachers and their families. Austin has confirmed that he isn’t planning on making vaccinations mandatory for returning teachers and students. We’ve heard repeatedly from teachers at board meetings that they feel unsafe going back to schools without a vaccine.

“As a teacher I am more than willing to get back into the classroom when it is safe,” Paul Gralen, Greene art teacher, said at the special board meeting on Feb. 2. “That means when my medically vulnerable family members have been vaccinated. It is profoundly unfair that I should be asked to put my family at risk.”

In addition, the Palo Alto Educators Association said that teachers should be vaccinated before returning to help keep them safe.

“Many districts around us are making arrangements to not come back in person until their teachers are vaccinated,” Terry Baldin, PAEA president, said at Tuesday’s board meeting. “Some of them are San Francisco, Los Gatos, Saratoga High and San Jose. We think that we should do this as well.”

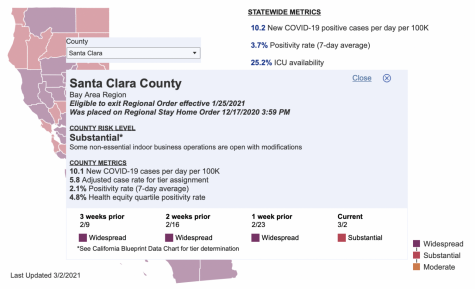

Thankfully, Santa Clara County has set up vaccination sites in the Bay Area to get educators vaccinated, although guaranteeing the shots before reopening would have been safer.

Austin has pointed out if students return and test positive for COVID-19, it would likely be due to activities that happen outside of school, so schools should not be blamed.

“I live here and I see groups of students together, sometimes in violation of guidelines that are out there by the county,” Austin said in a Jan. 21 interview with The Paly Voice. “If they come back and they have COVID, I don’t think it’s the school’s fault or responsibility. I think we get attributed to that number.”

However, Austin’s argument only goes to show how we cannot expect students to respect social distancing. The classroom is not the only place where the virus may be transmitted as students may interact after school hours while they are at or near campus. Reopening increases the likelihood of this taking place as it makes congregating in-person more convenient.

Since September, there have been a total of 52 in-person staff and students who have tested positive for COVID-19. Now imagine what that positivity rate will look like when we see an influx of in-person staff and students.

Furthermore, new strains of coronavirus may present a new threat.

Palo Alto Online reported earlier this month that the South African variant of COVID-19 that is more infectious than ever, has shown up in Santa Clara County. Thus, even in the best, unlikely case where the district can get teachers vaccinated, there are still new variants to be worried about.

The very basic principles of high school biology ought to be applied to our local politics. New strains will continue to evolve, and rushing reopening to increase contact would only accelerate the speed at which the virus can evolve and become resistant to vaccines.

Our community ought to value every single life, and not treat students and staff as statistics.

Collect the data before the plan

In his Superintendent Update on Feb. 12, Austin stated that “The desire to reopen has never faded and conditions may allow for the return of students soon.”

This highlights a key misconception. Those who prefer the status quo are less likely to speak out at board meetings since we already have a working distance learning system that has stayed in place for over a semester. Thus the “desire to reopen” is misrepresented in the pool of speakers at the board’s open forum.

According to a survey from Palo Alto High School Principal Brent Kline, 27% of freshmen and sophomore, 25% of juniors and 20% of seniors plan to return. This shows a significant increase since November, when 10% to 15% of students wanted to return.

However, these numbers don’t show the opinion of those who have no choice in the matter. Teachers who are mandated to return have had little say in the plan.

Reopening surveys should have to be mandated to collect the most holistic data possible, and account for the opinions of all those who are most directly affected — students and staff members. Additionally, data about how many staff and students want to return should be taken before plans are created to meet the needs of all the stakeholders.

Don’t treat reopening like a race. Widespread COIVD-19 infections might come back in the summer, or might come back in a year; we might even have to wait seven years, according to a Bloomberg study. However long that might be, we must fight the temptation to give up. We’ve already lasted one full year — let’s not put that to waste.

![In the fourth period AP Calculus BC class at Palo Alto High School, senior Crystal Li places her phone in the “phone jail.” Starting July 2026, this may become a normal procedure across schools in California thanks to Governor Gavin Newsom signing the Phone-Free School Act into law last week. According to Li, there are often unnecessary complications that come with enforcing phone restrictions. "It becomes a hassle putting it [a phone] in [the phone jail] before class, and taking it out after class," Li said. "There have been multiple times where kids from other periods interrupt the teacher to come back in and pick up a phone they left."](https://palyvoice.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/IMG_7386-3-300x225.jpg)

Bonnard • Mar 16, 2021 at 3:23 pm

Dear Jeffrey,

As a parent who supports school reopening, I think a less partial news article would be useful to the student community. It could take the shape of a pros & cons analysis of Stay home vs Return options. Among other factors, mental wellness should not be ignored, especially out of empathy for those who do suffer because of distance learning,

As important, I d like to point out that many in California and in Palo Alto seem to ignore the overwhelming evidence that schools around the world have reopened safely, including when Covid infection within the local community was high, before the virus vaccine and despite the variants. Such data-based evidence would bring objectivity to the discussion, and could alleviate the legitimate fear factor that seems to prevail.

Best, Matthieu

Radhika • Mar 16, 2021 at 2:09 pm

This is an opinion piece and it omits all the known science about school openings. All over the world it has been shown that schools do not contribute to transmission. Our own elementary schools have been open since October with ZERO transmission. The writer should check Palo Alto data and present facts. The CDC is about to reduce the distancing requirements in schools because of low transmissions in schools.

The writer must state this is a personal opinion and is not data based. Our county (which has been the strictest in California) and state allows schools to open in red tier so to say that it is unsafe is spreading fear. An expert panel of UCSF and Stanford experts clearly provided information showing it is entirely safe to open schools. Pediatricians all over California have asked for schools to be open. The writer must provide data and science to back up any claims.

Furthermore covid anxiety is not the only anxiety. Kids have been suffering from isolation and depression for a year. A recent Palo Alto online article revealed the amount of toxic stress lockdowns and schools closings have put on students. None of that is addressed in this – this is not a fact based piece.