Opinion: Mandatory assemblies matter, but students need to believe they do

December 6, 2018

Hundreds of students trudge into Palo Alto High School’s Performing Arts Center, having just been excused from English, orchestra or algebra to sit in an auditorium for 90 minutes. They fill the rows of seats like ranks of soldiers awaiting a drill sergeant. Moments later, the guest speaker walks onto stage, all smiles and cracking lame jokes. There is scattered applause, then silence as the speaker begins his or her spiel about the topic of the day, whether it’s gender roles, sexual assault, or substance abuse.

Pointing fingers at the Paly administration for forcing students to sit through such boring instruction, however, offers an incomplete verdict. In fact, both parties — the administration and the students — need to reexamine their approaches and their views on mandatory assemblies.

Firstly, the Paly administration itself has little choice in holding mandatory assemblies dedicated to sexual assault. The assemblies that students attended in February and April are organized by PAUSD’s Responsive Inclusive Safe Environment task force, which then-interim Supt. Karen Hendricks established in 2017 to oversee Title IX compliance and provide sexual assault prevention education to PAUSD high schools, according to an article by Palo Alto Online.

Secondly, there’s no question that to achieve maximum student participation, the assemblies need to be mandatory. Going to assemblies during a class period is unpleasant for everyone. It frustrates both teachers and students as precious instructional minutes are spent lecturing students on topics like consent or sexual assault that have been rehashed over and over again since fifth grade.

But let’s face it: If assemblies weren’t during a mandatory period, nobody would go. Students have an aversion to (and I can say this with absolute authority, because I am one of them) doing anything that isn’t required and won’t directly provide a grade or some other kind of gratification in the near future. If the assembly were held during a Tutorial period or after school, few students would bother to show up. On Safe and Welcoming School Day (Aug. 31), a minimum day devoted entirely to educating students on topics including bullying and digital citizenship, student attendance was strikingly low.

Missing a single period of instruction is something teachers should easily be able to work around. After all, the class time lost to the numerous false fire alarms that have occurred this year alone is similar to the amount of class time lost to assemblies, and unlike a false fire alarm, teachers can plan around a mandatory assembly in advance.

When asked about whether or not planning around mandatory assemblies is difficult, science teacher Vivian Byun said that teaching a mixed class with students from multiple grade levels posed a challenge.

“But I see the value of the assemblies, so I’m happy to accommodate,” Byun said.

That being said, students’ concerns about scheduling conflicts are very real, and should not be ignored by the administration. The coming assembly on Thursday is inopportunely placed less than two weeks from final exams, making it another headache students have to deal with. Assemblies should occur in the middle of the semester, away from grading periods and other sources of student stress, and administrators should give teachers plenty of warning beforehand so that they can organize lessons accordingly.

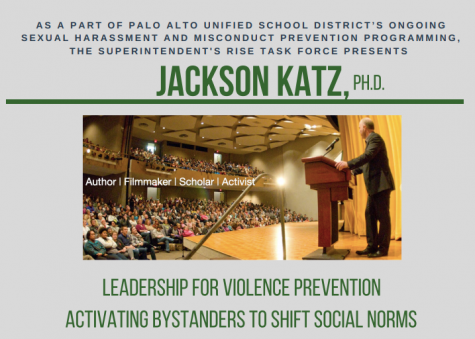

Finally, to the heart of the matter — an assembly, presentation or lecture means nothing if the students themselves don’t care. Students should show respect and pay attention to the speakers, who are taking time out of their days to educate us on topics that they care deeply about, even if their beliefs brush up against some of the students’ own. Even when this happens, heckling and jeering speakers in a manner similar to the reception Jackson Katz received during a series of lectures in April shouldn’t become the norm.

“I think the messages that they [speakers such as Katz] are trying to spread are obviously good, and I don’t know another way that they could do that more effectively, but I don’t think it really sticks with students, and I feel like people just make fun of it,” senior Galileo Defendi-Cho said. “If attendance wasn’t mandatory, I think a few people would go, and those people already believe in the messages that they [the speakers] are trying to convey.”

Although the burden is on the school district to find effective speakers who engage students, and the school district makes mistakes occasionally, that is no excuse to condemn all mandatory assemblies entirely. If students don’t choose to listen or internalize the lesson, not only are they wasting the speaker’s time, but also their own.

We can all agree that mandatory assemblies aren’t perfect and are headaches for both students and teachers. But as unpleasant and annoying as they are, they are still useful sources of education, and students should view them as such.