Is an earthquake coming? Experts say it’s likely

January 18, 2018

The timing of an earthquake preparedness panel at 6:30 p.m. tonight in the Palo Alto City Council Chambers is on point after a 4.4 magnitude earthquake on Jan. 4 in Berkeley rekindled concerns over a future large-scale seismic event.

The event, titled “Calamities Happen: What You Need to Know,” will feature experts Brandon Bond from Stanford Health Care, Tom Brocher from the United States Geological Survey, and Jeff Norris from San Mateo County’s Office of Emergency Services, according to the City of Palo Alto.

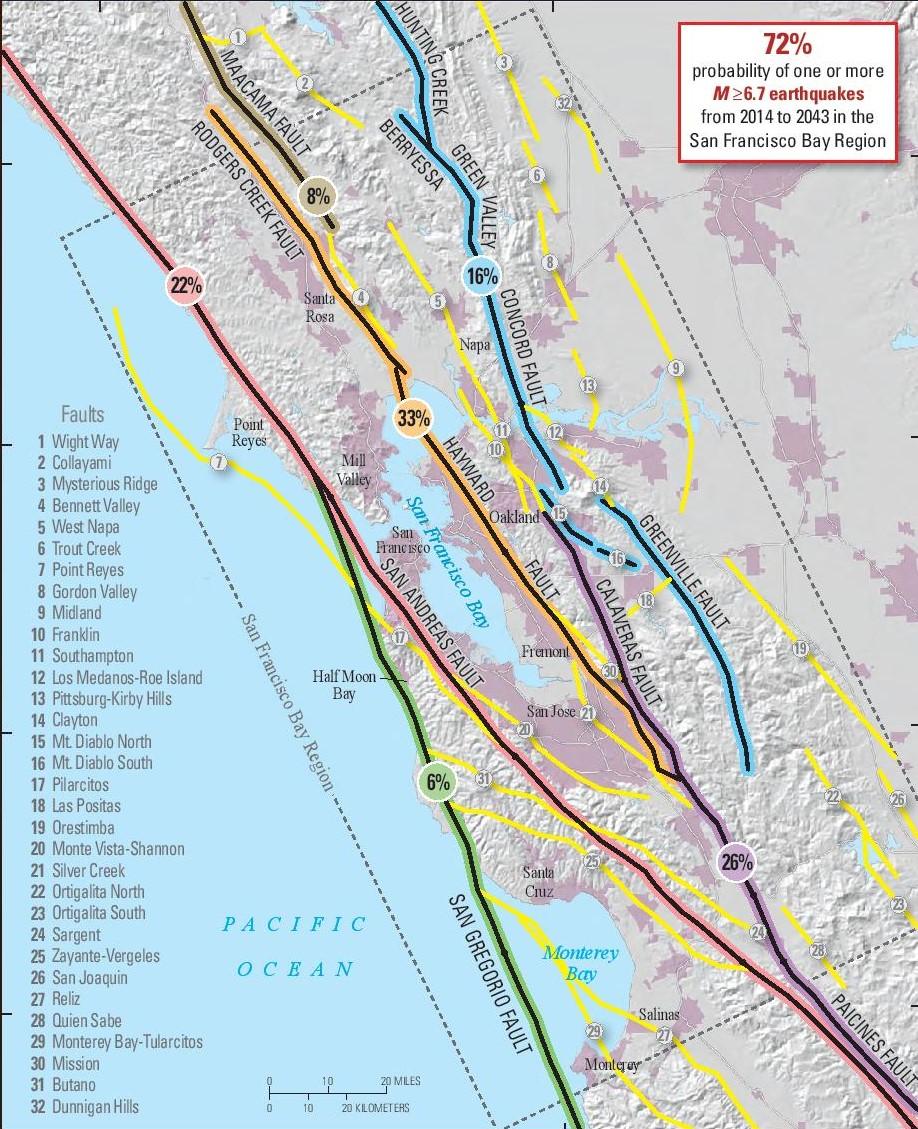

According to the U.S.G.S., there is a 72 percent chance that the Bay Area will experience at least one earthquake of magnitude 6.7 or greater by the year 2043.

“For the major parts of Southern California and the San Francisco Bay Area, we have a pretty high probability of earthquakes and we could get a large earthquake at any time,” said Ruth Harris, supervisory research geophysicist at the U.S.G.S. “So in the next five seconds we could have a large earthquake and it would not be surprising.”

While Harris remains concerned about earthquakes along the San Andreas Fault, she dispelled a common misconception among Bay Area residents.

“San Andreas Fault is very active, and it [an earthquake] would not at all be a surprise, but that’s almost the one that people are always expecting,” Harris said. “In the Bay Area, though, it’s actually the Hayward Fault that we’re very worried about because of its location in a very densely populated area.”

The Hayward Fault runs through areas such as the East Bay and Memorial Stadium, located on the campus of University of California, Berkeley. According to Harris, the fault is relatively active.

“We’ve been concerned about the Hayward Fault for at least 20 years now,” Harris said. “It had a big earthquake in 1868, and then two of our geologists did some digging on it […] and they dug these big pits across the fault. They saw that the fault goes pretty often, about every 150 years or so.”

A release of energy along a fault line could cause an earthquake, according to Harris.

“Plate tectonics are driving the motions in the faults which have all this energy kind of stored up,” she said. “If you have a rubber band and you’re stretching it, although that’s not exactly how the Earth’s crust works, it has to snap at some point. We think of faults as storing up all this elastic energy, and it has to be released.”

Both Harris and Alicia Szebert, an AP Environmental Science teacher at Palo Alto High School, stress the importance of formulating a plan to prepare for an earthquake.

“If you haven’t ever thought about it […] and there’s an earthquake, it’s a lot easier to panic and stress and not really go somewhere safe than if you had premeditated what you want to do,” Szebert said.

According to Szebert, among the most important factors to consider while creating a plan is whether any large or heavy objects around you will collapse. Avoiding and planning around such hazards can decrease the probability of injury.

“Think about where you would go and what would be a safe place for you to go, and make sure you’re watching out for your other classmates during a disaster situation,” Szebert said. “It’s about focusing on what’s going to collapse and what would be the safest place if collapsing happened.”

Szebert advises against running to an exit unless it is nearby and readily available.

“In a very extreme earthquake, the ground itself is moving in a circular motion,” Szebert said. “If the earthquake is bad, you will not be able to literally run outside, so you want to get to your safe area as quickly as possible.”

Harris also emphasizes the importance of being aware of one’s surroundings, especially in populated areas, to ensure safety during a disaster.

“If you’re in a classroom go look around,” Harris said. “Every time I go into a building I’ll look and see if there is any heavy equipment over me.”

As most students within the Palo Alto Unified School District have experienced earthquake drills since kindergarten, Szebert believes that the level of preparation practiced in the district is appropriate, but urges students to consider preparing plans in each of their classrooms.

“The real event will never be exactly what we think it will be […] there will be a lot of surprises,” Harris said.

If you would like to learn more about how you can prepare for an earthquake, visit the Red Cross and the Earthquake Country Alliance websites.