We gather at Bolivar House, home to the Center for Latin American Studies at Stanford. People are crowding doorways and streaming out the front door, sitting down on the carpet next to the podium and ducking under glaring camera lenses. There is a feeling of informality so typical of Latin America that it seems to band the whole group together under the weight and tension that accompanies the event. The event begins with a series of presentations, during which a father valiantly comes forward to share a few words with the group. We don’t know the man any better than we know the rest of of the crowd, but we band together under his pain because his pain is our pain; his grief, the grief of all of Mexico.

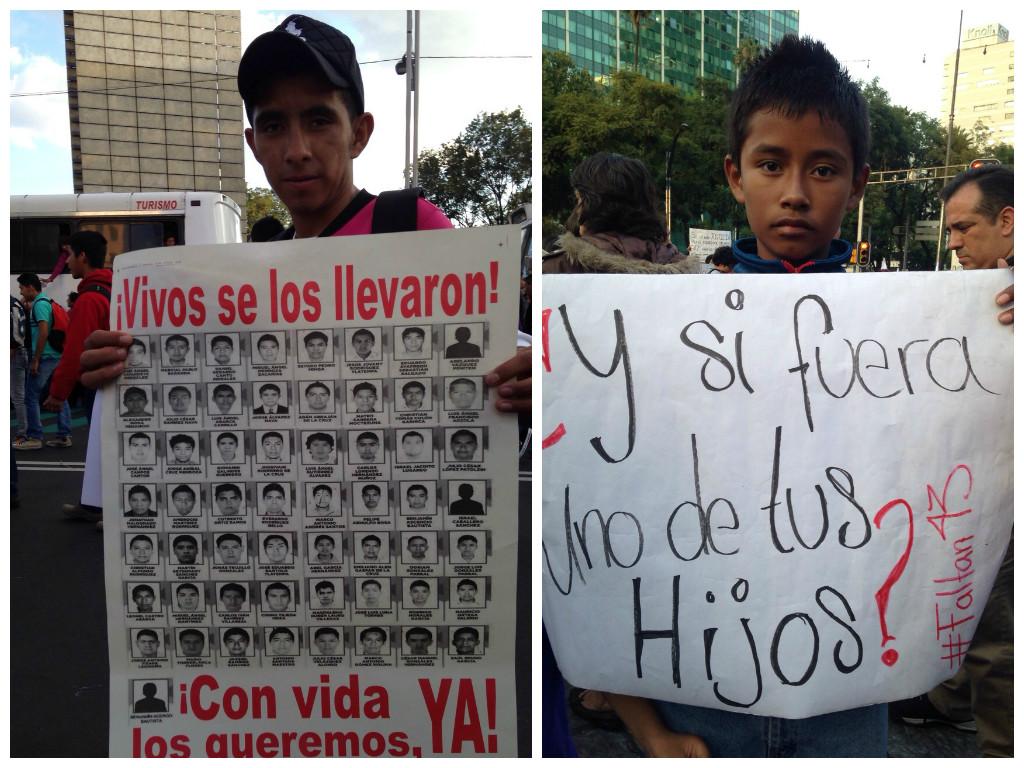

This was a few months ago when I was attending a vigil at Stanford University at the Center for Latin American Studies to honor and inform people of the 43 missing students of Ayotzinapa, Guerrero. According to South American television network teleSUR, the students were arrested by Mexican police and then turned over to local drug gang Guerreros Unidos. When these students disappeared, a connection was drawn between the police who arrested them and the Mexican drug cartels. According to teleSUR, authorities believe that the students were killed.

Occurrences similar to this massacre have become common over the last 10 years in Mexico’s drug war. However, this event has brought to light a connection between the Mexican government and drug cartels, serving as a wake-up call for not only Mexicans but also for people all over the world. Mexicans and non-Mexicans alike are saying “basta” or “no more” to the death, the corruption, the disappearances and the abuse of power the Mexican government seems to wield.

The reaction to the disappearance of these students has exploded into a movement for social change across Mexico and the world, rallied by students of all ethnic backgrounds against the corruption of the Mexican government and its increasingly translucent connection with the Mexican drug cartels. Since the disappearances of the students in Ayotzinapa, there have been hundreds of non-violent protests all over Latin America, many of them still ongoing today.

More than 100 people attended the Stanford vigil, Hispanic and non-Hispanic alike. I was glad to finally see people in my community act. Being from Mexico, the Mexican drug war has always been an issue prominent in my life, and the overwhelming support from the Bay Area community was something I had yet to experience. I felt very moved and empowered by the event.

It’s disappointing how little American news channels have covered the events in Ayotzinapa. At school, I was surprised by the fact I was one of the few people who knew about the tragedy and the movement for social change. It makes sense, coming from Mexico, that I be informed on this topic; however, it doesn’t meant that everyone else in Palo Alto should be oblivious to a tragedy that is happening right next door, in a country whose border we share. After asking around, I was also surprised by our community’s lack of education on the Mexican drug war in general and other drug wars happening all over Latin America

Thirty-eight percent of California’s population is Latino, and towns in the Bay Area such as Redwood City and East Palo Alto have huge Latino communities. Yet, there is a profound disconnect between the United States and Mexico. Violence in Mexico is not really highlighted by the media, and as a result, the few times that these issues are discussed, it is often in blind ignorance. Perhaps this is caused by the distraction of events in the Middle East. Perhaps people believe it does not affect them, or perhaps the fact that violence is happening a road trip away makes them feel uncomfortable and vulnerable.

Regardless of the reason, violence in Mexico is not often covered by American media. Real violence by real people in a very real proximity to the United States is often left ignored, and what doesn’t appear on the screens or in the papers ceases to exist in the minds of the American people.

This has to change because these events affect more than just the families of the those 43 missing Ayotzinapa students. They affect your gardener, the guy who bags your groceries at Safeway, your doctor, that student who sits next to you in class, your nanny.

We should address these issues not as far off problems, but as issues deserving of our attention that affect us in in California, right here and right now, even if they’re not highlighted by the media. We should give our Mexican neighbors the global support they deserve.