Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli has made fewer and fewer masterpieces over time. Comparing “The Boy and the Heron,” Studio Ghibli’s latest film released on Dec 8, to the classics “Totoro,” “Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind,” and “Princess Mononoke” is difficult — some good similarities are apparent, yet the aspects that made those films most appealing seem missing in the new one. Setting aside the plot holes in “The Boy and the Heron,” Studio Ghibli’s animation has only improved since its first movies and the moral lessons learned have become easier to understand.

The visuals in Studio Ghibli’s films have definitely improved over the decades that it has been making movies. Each individual frame is closer together, the depth is much better with the background moving slower than the foreground, and the film overall feels more like an animation than drawings after drawings as Studio Ghibli’s films have been in the past.

The musical score, composed by the legendary Joe Hisaishi, complements the narrative beautifully with deep single-note vocals and fast-paced orchestral symphonies. Hisaishi’s melodies tug at the heartstrings, enhancing the emotional impact of key moments and adding an additional layer of magic to the film. The sound design, bringing to life the enchanting whispers of the wind and the rustling leaves, further immerses the audience in the enchanted world of “The Boy and the Heron.”

One thing held consistent over the years in Studio Ghibli productions has been plot construction, as the storylines are largely flawless with little holes. Set in Japan during World War II, this latest film opens with the main character, Mahito, moving into a new village with his father. There, Mahito is introduced to his new stepmother — however, he finds himself unable to move on from the death of his mother three years ago. Mahito’s words and actions show his unwillingness to accept his new situation. As Mahito is lured by a talking gray heron into a magical tower on the promise of answers about his mother’s death and to solve the kidnapping of his stepmother, the viewer is taken on a journey through time and space to a different world where a tower of blocks built by his great granduncle controls the balance of the planet.

Mahito’s relationships with those around him, most notably his stepmother, are developed over one long adventure, and the story is brought to one complete circle in the last scenes. The moral of the story is solidified at the end, with the idea that one must accept and learn to love those around them and the world they live in. No complaint can be taken with the cohesiveness of the timeline. However, one aspect of the movie’s plot, centered around Mahito’s character, leaves behind a feeling of disbelief and confusion.

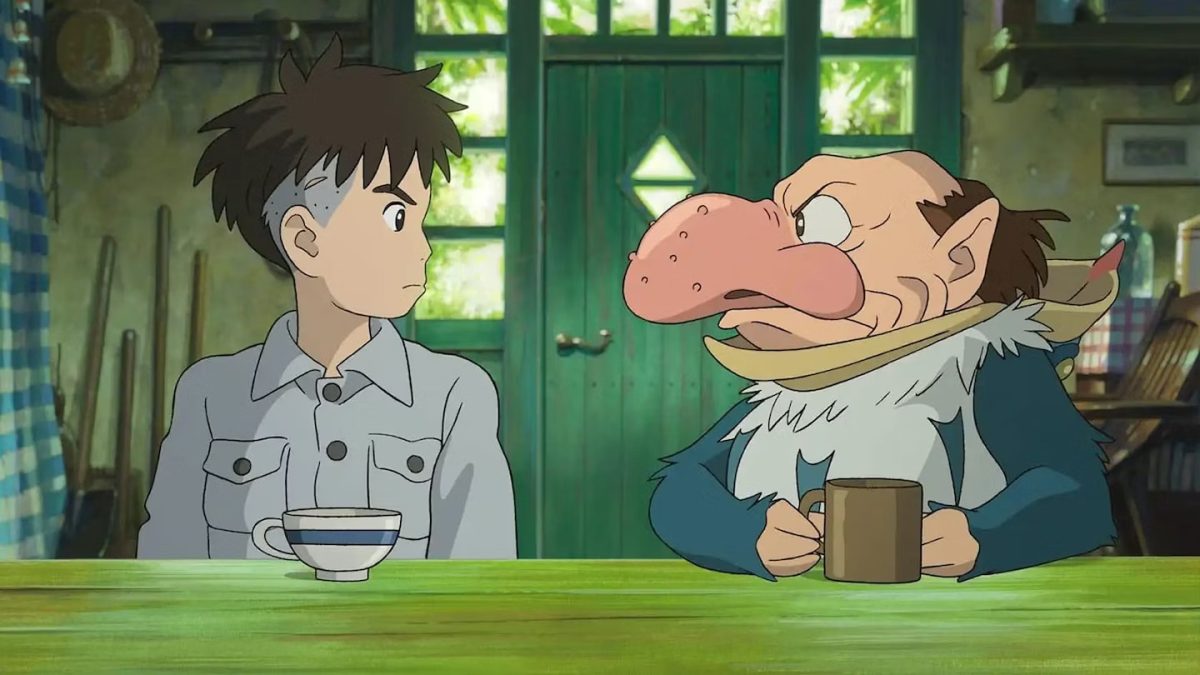

Despite the fantastical nature of the world Mahito finds himself in, he never questions the abnormal circumstances he finds himself in. He is brought into a different world through an invisible door by a big-nosed man living as a heron. The world is filled with killer pelicans, voracious parakeets and thousands of warawaras (small, white creatures) that each represent a human that has yet to be born. He is led on his journey to find his lost stepmother out of respect for his father and possibly the secrets to his own mother’s death, all by a girl who eventually turns out to be a younger version of his mother — with magical fire powers. The balance of a tower of blocks controls the fate of the world itself. Even with all this, he never asks, “Where am I?” “Who are you?” “What am I doing here?” or even “How do I leave?” Mahito simply just seems able to accept everything at face value. As Mahito is a 12-year-old, coming from such a young kid, his startling lack of curiosity and confusion takes away from the realism of his character design. Had he been older, it would have been understandable — yet as a child, the startling lack of curiosity he has about his circumstances is a massive hole never explained.

Despite the viewer’s immersion being frequently tested, the film still is able to deliver its message in a profound way, without resorting to heavy-handedness. The themes of accepting where you are, learning to love the good things in your life and the people around you are seamlessly woven into the narrative, with Mahito calling his stepmother “mother” for the first time and opting to leave the opportunity of building his own perfect world behind in favor of living in the real one. Studio Ghibli remains solid in its ability to offer subtle yet powerful reflections on the state of our world.

All in all, “The Boy and the Heron” stands as a testament to Studio Ghibli’s enduring ability to captivate audiences with its enchanting tales. With its stunning animation, heartfelt storytelling and timeless themes, this film is likely to join the ranks of Studio Ghibli’s classics, as its biggest flaws fail to take away significantly from the majesty of the work overall. Ignoring the oversights of Mahito’s character development, it remains a cinematic journey that is both enchanting and inspiring, urging us all to cherish the delicate balance between humanity and the natural world.