Creeks in the Palo Alto area are brimming with water after a series of storm systems drenched much of California this past winter.

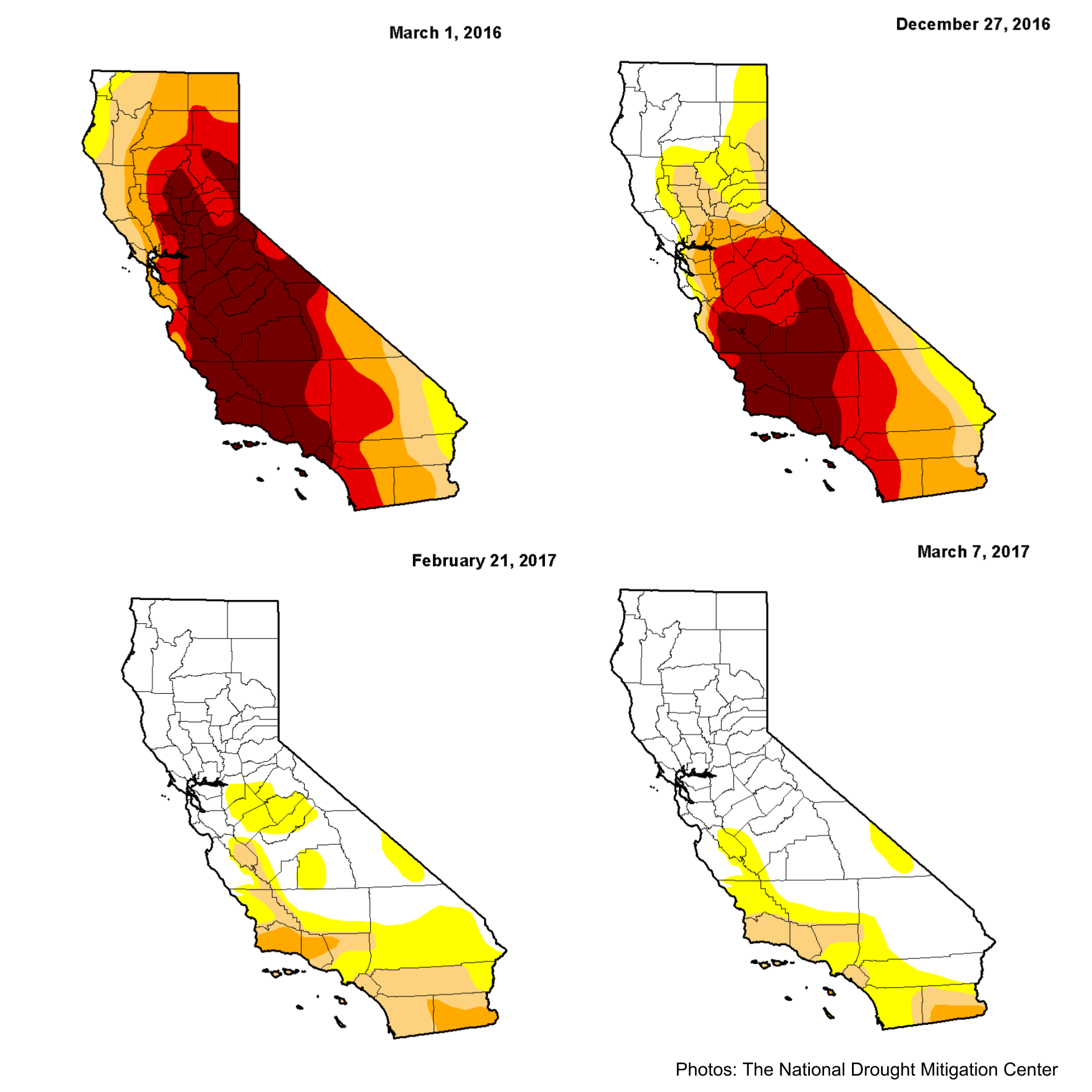

Last week, over 15 million people in the state officially lived in drought, especially in southern California. Today, that number has dwindled to slightly under 10.5 million, or 27 percent of California’s population. While the drought has been lifted from much of the north, the southwest remains relatively dry, according to the United States National Drought Mitigation Center.

The recent storms have caused record-breaking levels of precipitation in areas across the state. Long Beach and Los Angeles Airport set an all-time record for rainfall in January, while Mercury News reported that California is in the midst of its wettest water year in 122 years.

The average rainfall in California is 50 inches, though an environmental phenomenon called “La Niña” has brought over 68 inches of rain as of mid-February, according to CNBC. The plentiful rainfall triggered a dam in Oroville, Calif. to use its emergency spillway for the first time in its nearly 50-year-old existence.

Infographic: Jevan Yu.

Recent storms, which steadily eroded the six-year drought, have dramatically affected Palo Alto’s ecosystems.

According to Richard Bicknell, one of Palo Alto’s Byxbee Park rangers, the drought has taken a steady toll on local parks for roughly six years. Native vegetation in the Palo Alto Baylands, for example, suffered from the lack of rain while invasive species such as mustard and fennel, whose deep roots provide for better safeguards against the effects of drought, thrived in comparison. Native plants are beginning to flourish once again due to increased precipitation this past fall and winter, with some species increasing in number by 500 to 600 percent, he says.

“We’ve seen more birds, insects, more lizards, things like that — many more of the small animals,” Bicknell said.

The drought also caused significant economic losses across the state. According to a University of California-Davis study, the drought resulted in a $603 million loss of agricultural revenues and 4,700 jobs statewide in 2016 alone. This cost includes crop revenue losses, the cost of additional water pumping to the Central Valley and minor dairy and livestock revenue losses.

Advanced Placement Environmental Science teacher Nicole Loomis elaborated on the economic impacts of the drought.

“When you don’t have water you can’t make as much hydroelectric power and you have to rely on other sources,” Loomis said. “You have to pay more to irrigate your crops and food prices go up. … The groundwater is going to take a long time to recharge. There was a lot drawn out during the drought.”

Despite recent rains, Bicknell recommends that Palo Altans continue to limit their water use.

“It’s a very good idea to keep down water use,” Bicknell said. “You can use reclaimed water, which is what we use to water with. Use your water sparingly. Don’t take a three-hour shower; try to hold yourself to 10 minutes, because you never know, it may not rain next year. The water tables are all recovering and our reservoirs are fairly full but … you never know when the drought may start up again.”