Opinion: A detailed analysis of Stanford’s GUP deal

October 21, 2019

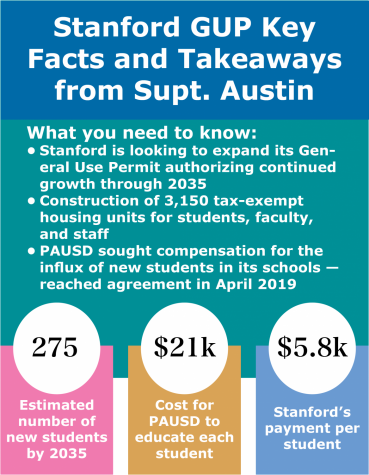

Talks between Stanford and the Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors regarding the General Use Permit will resume Tuesday the second of four total hearings held to reach a deal to increase housing on Stanford’s campus.

Stanford and the Palo Alto Unified School District reached a separate deal in April, which would, if codified into the GUP, introduce the district new students who will come with the new housing. Stanford will pay a total of $138 million over 40 years to mitigate the effects of enrollment from the new proposed housing units.

The issue has sparked outrage among some members of the Palo Alto Community over its potential impacts on the school district’s budget. According to an article by the Palo Alto Online in March 2019, dozens of parents, teachers, and school district volunteers held a rally demanding “full mitigation.” Essentially, they demanded for Stanford to fully pay for the cost for PAUSD to educate the new students under the proposed housing expansion. The Palo Alto Parent Teacher Association has also made similar demands for full mitigation.

County Supervisor Joe Simitian, who represents the district that includes Stanford, told the Mercury News in September that “County staff has recommended that supervisors approve Stanford’s expansion request as long as the university agrees to completely mitigate its impact on local schools, traffic and housing.”

The Financials of the Deal

However, what Stanford and the district agreed on is far from full mitigation.

The average household in Palo Alto only contributes roughly $6,000 annually in property taxes, according to Superintendent Don Austin, who negotiated the deal. The district spends an average of $21,000 per student because most Palo Alto properties do not house students, but they still pay property taxes that go to the district, Austin said. Under the deal, Stanford will only pay $5,800 per K-12 student living in Stanford housing who attend PAUSD schools. Since Stanford property is tax-exempt, there is no more property tax to compensate for the additional $15,200 needed to educate the incoming students.

While the district and Stanford officially estimate that the new housing units will generate 275 additional students by the year 2035, Austin expects the actual number of incoming students to be much larger.

“It’s going to be 250 [students] somewhere around year 4,” Austin said. “And that number will hold pretty true until year 10 — 10 years out, we’re expecting at least 500 students and probably more.”

According to Austin, the recent declining PAUSD enrollment will compensate for the large influx of students from Stanford housing units.

“This year we lost about 260 students,” Austin said. “It’s not like we’re maintaining the same number of students and then adding Stanford students. We’re also declining in residents so it’s not going to be a net of 500 students — overall, it’s going to be a wash.”

According to Austin, the decline is largely due to an aging demographic, and the fact that appreciating housing prices out younger families who are more likely to have school-age children. However, as opponents of the deal point out that there exists little evidence to support a long term decline in enrollment at PAUSD. The Stanford GUP Briefing Book, written by Austin and his staff in January 2019, notes that the Palo Alto Comprehensive Plan (Palo Alto’s main plan for land development), “calls for at least 300 new housing units a year for the next 12 years,” and “points to enrollment growth resuming” in Palo Alto schools.

According to the Briefing Book, “PAUSD enrollment has declined by about 4% over the last 5 years, after 25 years of continuous growth. But all signs point to enrollment growth resuming and even surging as the city, county, and state work to address the regional housing crisis.”

Using a rough estimate of 12,000 students enrolled in PAUSD, if PAUSD enrollment did continue to decline at the same rate of 4% over 5 years, this would result in a loss of 480 students in the first 5 years, which could compensate for Austin’s estimate of an increase of 250 students for the first 4 years. While declining enrollment could theoretically mitigate for the additional Stanford students in the short term, it would not be able to compensate if the enrollment rate increases in the future as the Briefing Book predicts, or if Stanford decided to add more housing units.

With the negotiations still underway, it is unclear how many housing units Stanford may be permitted to build, and such uncertainty jeopardizes the viability of PAUSD’s deal with Stanford.

Historical Background and Comparison to the 2000 Stanford GUP

Austin argues that the new deal is a substantial improvement in contrast to the last Stanford GUP agreement, in 2000, mainly because Stanford agreed under the new deal to mitigate the impacts on PAUSD enrollment on a per-student basis.

“Stanford has never provided ongoing funding on a per person basis for any school districts in the history of Stanford,” Austin said. “So when I went in [for negotiations with Stanford], the expectation from lots of other people was that we were not going to be getting any ongoing funding.”

According to Austin, Stanford is not legally obligated to pay for any mitigation.

“Stanford only owes us through statute — called impact fees — which are per square foot,” Austin said. “Without these perks [from the current $138 million Stanford GUP agreement], Stanford would only owe us between $4 and $5 million — somewhere in that ballpark.”

In addition, Austin argues that Stanford is already providing numerous community benefits to Palo Alto schools. For example, Stanford — primarily from Stanford Shopping Center — pays $30 million in taxes per year in residential and commercial leases to PAUSD. The district also leases roughly 50% of its land from Stanford at low costs, and PAUSD retains a number of partnerships with Stanford educators.

Specifically, Austin points to the comparison between the values of the two deals as a key reason the new deal is a substantial improvement.

“The last time the district did a GUP deal, the district got $10 million as a one-time payment,” Austin said. “Now, our floor is somewhere around $148 million. And if they send more students — which I fully expect — it could be quite a bit higher than that.”

It is worth putting the two GUP deals — 2000 and 2019 — into perspective. In the Stanford GUP deal in 2000, Stanford agreed to make a one-time payment of $10 million to mitigate an estimated enrollment of 550 students. In practice, the expansion under the 2000 Stanford GUP deal only introduced a total of 50 new students into the Palo Alto school system, and the extra money gained from the deal was significant enough to buy and open what was at the time Terman Middle School (now known as Fletcher Middle School). While the 2000 Stanford GUP deal worked in PAUSD’s favor two decades ago, there seems to be no mechanism in place for preventing poor estimations from hurting the 2019 deal.

The school district hearing on the Stanford GUP deal will begin at 6 p.m. Tuesday at Palo Alto City Hall, 250 Hamilton Ave.